TAM is fast approaching, and I’ve been frantically trying to get my talks together. The theme this year is “Fighting the Fakers,” and one of my talks will be for the Science-Based Medicine Workshop on Thursday, in which I will attempt in a mere 15 minutes to explain what Science-Based Medicine is and how it can be used to combat the infiltration of quackademic medicine into medical academia. Then, the second talk will be a tag-team spectacular with Bob Blaskiewicz about Stanislaw Burzynski as an example of how some cranks skirt the edges of science-based medicine. That doesn’t make them any less dangerous (if anything, it makes them more dangerous), but it does make them not as easy to identify as someone like, say, Hulda Clark.

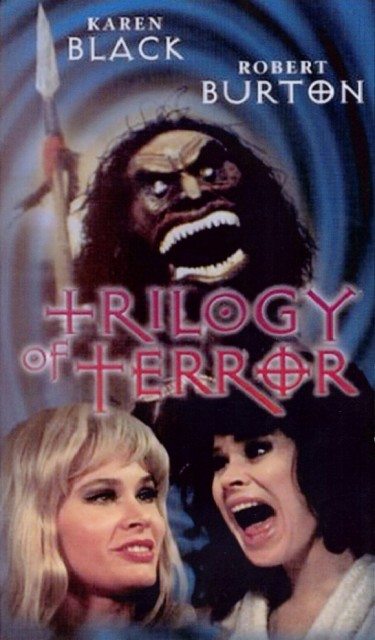

Unfortunately, between working on these talks, revising some papers, and having an unusually busy weekend on call, I wasn’t sure what I was going to come up with for the edification of you, our readers. Fortunately, right on the 4th of July holiday, there was an article that gave me my idea, particularly given that I had noticed a couple of studies on the very subject of the article in the week leading up to the long holiday in the US (at least for people not on call). As a result, I’m half tempted to refer to this article as a trilogy of acupuncture terror.

Oh, wait. I just did.

Book I: Acupuncture is harmless, right?

One myth that acupuncture apologists like to promote relentlessly is that acupuncture is completely harmless, that it almost never causes complications or problems. While it’s true that acupuncture is relatively safe, it still involves sticking needles into the skin, and, given that, it would be delusional to think that it couldn’t cause injuries. Rarely, however, have I seen a story like this in the Canadian newspaper the National Post, “Canadian Olympian’s ‘nightmare’ after acupuncture needle collapses her lung“. It is the story of what happened to Kim Ribble-Orr, a world-class judoka who had competed in the Olympics in 2000 and was harboring dreams of competing in the Olympics again, as a mixed martial artist. Those dreams were cast in doubt by a stray acupuncture needle:

When a massage therapist tried to treat the headaches she suffered after a 2006 car crash with acupuncture, however, he set off a cascade of health problems that would shatter Ms. Ribble-Orr’s sports-centred life — and raise questions about the popular needle therapy.

The therapist accidentally pierced Ms. Ribble-Orr’s left lung during acupuncture treatment that was later deemed unnecessary and ill-advised, causing the organ to collapse and leaving it permanently damaged. An Ontario court has just upheld the one-year disciplinary suspension imposed on therapist Scott Spurrell, rejecting his appeal in a case that highlights a rare but well-documented side effect of acupuncture.

Mr. Spurrell, who learned the ancient Chinese art on weekends at a local university, had no reason to stick the needle in his patient’s chest, and had wrongly advised Ms. Ribble-Orr that the chest pain and other symptoms she reported later were likely just from a muscle spasm, a discipline tribunal ruled.

Ribble-Orr had suffered many injuries due to her competition, including a dislocated elbow and shoulder, a broken hand, head injuries and repeated knee injuries. She had overcome them all to compete again, but appears unable to overcome this one. Basically, what happened is that in 2006, Ribble-Or was trying to get into mixed martial arts competition and was eying a job as a police officer. However, she was also recovering from injuries suffered in an auto collision and seeing Scott Spurrell, a massage therapist who had learned acupuncture during a weekend course at a local university. She was suffering from pounding headaches, and Spurrell convinced her that he could relieve those headaches by inserting a two-inch needle, according to the disciplinary ruling, “into a muscle located between the clavicle bone and ribs.” From the description, it’s not clear to me exactly which muscle they meant, although it could conceivably have been the scalenes, the sternocleidomastoid, or perhaps even just the pectoralis major. Whatever muscle Spurrell was targeting, going between the clavicle and the ribs is basically where surgeons stick the needle when trying to place central venous catheter into the subclavian vein, and, yes, a pneumothorax is a known potential complication of placing such lines. What also puzzles me is how on earth Spurrell could have stuck the needle in deep enough to cause a pneumothorax? It would be one thing if Ribble-Orr were a fragile little old lady, but she wasn’t. She was an athlete, presumably with well-developed musculature. It would take a lot to get a needle through all of that muscle and into the pleural cavity.

As can happen from a pneumothorax, even in a healthy person, Kibble-Orr developed pneumonia and required a thoracotomy. To be honest, it’s not clear from the account provided why she needed a thoracotomy, but it’s clear that the pneumothorax led to a cascade of complications, as described:

Shortly after leaving the clinic, Ms. Ribble-Orr began having difficulty breathing, chest pain and a “grinding” sensation. She returned to the therapist later, wondering if she had suffered a pneumothorax. He told her it was more likely a muscle spasm, but said she could go to the hospital if she felt it was more serious or if the symptoms worsened.

The next morning, she did feel worse and finally headed to the emergency department. Ms. Ribble-Orr’s lung had indeed collapsed and she spent the next two weeks in hospital, as a serious lung infection and then a blood infection followed. She was left with just 55% function in one lung.

One notes that if you do not have the knowledge to recognize symptoms and signs of potential complications resulting from your treatment, you have no business administering that treatment. It used to be that if you didn’t know how both to recognize and treat potential complications of your treatment, you shouldn’t be administering that treatment, but those days are gone. For instance, gastroenterologists do colonoscopies, even though they are not able to repair the inevitable (and thankfully uncommon) colon perforations that are a recognized risk of the procedure. But they can recognize the signs and symptoms. They know how to diagnose a potential perforation and when to call a surgeon to fix it. Spurrell was clearly utterly clueless, basically dodging responsibility by telling Kibble-Orr that she could go to the ER if she wanted to. Obviously, he didn’t think that she needed to. What should have happened, if Spurrell knew what he was doing, was a quick physical exam, which likely would have diagnosed a significant pneumothorax through decreased breath sounds or elevated diaphragm on the affected side, or both.

While the ruling against Spurrell is heartening, what is rather depressing is how Canadian authorities came around to it. Acupuncture is a licensed specialty. So authorities had to “prove” that Spurrell had no valid reason to insert a needle there (“valid” being defined within the system of traditional Chinese medicine undergirding acupuncture). In other words, they had to show that there was no reason under TCM to think that a needle stuck in that particular location would treat Kibble-Orr’s recurrent headaches. Moreover, it wasn’t the College of Acupuncturists who had jurisdiction, but rather the College of Massage Therapists, and the College only requires a certain number of hours of extra training to be able to administer acupuncture, a requirement that Spurrell had met. Of course, we at SBM would argue that there’s no science-based reason at all to think that sticking a needle in a point between the clavicle and the ribs would have any effect whatsoever on recurrent chronic headaches, and that should be enough. That’s the problem with regulating quackery; to prove misconduct or malpractice, you have to do it within the system of magical thinking of the quackery that has been licensed. If, for instance, Spurrell had been able to show that there was a valid rationale under TCM for inserting the needle there, he still might have been nailed for incompetence because he stuck the needle in too deep, but quite possibly he might not have been.

Particularly depressing are the comments. For instance, one commenter named Dr. Joanny argues:

Only a bonafide doctor of Chinese medicine or acupuncture is qualified to practice Chinese medicine. The problem is not acupuncture but who is inserting the needles into your body. Only someone who has trained and studied for several years, who has passed board/state/provincial exams, is qualified to practice. All reports of puncturing lungs involve people who are people who took a little bit of training.

Yes, this acupuncturist is seriously arguing that “well-trained” TCM practitioners wouldn’t have had this complication and then goes on to cite a paper from a very acupuncture-friendly source that shows a surprising number of serious complications from acupuncture, including cardiac tamponade, infection, various reports of needles breaking off and migrating elsewhere in the body (shades of the President of South Korea!), and even neurological injury. One remembers a recent review of the Chinese literature by Edzard Ernst describing complications of acupuncture, including pneumothorax (201 cases), spinal epidural hematoma (9 cases), subarachnoid hemorrhage (35 cases), right ventricular puncture (2 cases), intestinal perforation (5 cases), and a whole lot of other complications and infections. Indeed, Ernst found that pneumothorax was by far the most common significant complication of acupuncture, and, as we’ve discussed, acupuncture is not harmless. There are quite a few potential complications up to and including 90 deaths in the world literature.

All medicine is a risk-benefit analysis. All effective treatments have risks, and those risks have to be weighed against the potential benefits. When the benefits are significant (e.g., saving life), then greater risks are tolerable. When the potential benefits are minimal, then even minor risks might not be acceptable. When the potential benefits are none, no risk is acceptable. That is the case for acupuncture. It does not work, no matter how much acupuncturists try to prove it does.

Books II and III of The Trilogy of Acupuncture Terror are simply more evidence that this is true.

Book II: In which regression to the mean in a subgroup is mistaken for a real result

That acupuncture is nothing more than an elaborate placebo is now quite clear. In any case, none of this stops acupuncturists from claiming they can help in conditions with “hard” endpoints, such as in vitro fertilization for infertility. It’s all Tooth Fairy science, but they keep trying, and so they tried again recently. At least, Brian Berman tried again. Berman, as you might recall, makes his quackademic home at the University of Maryland, and last week my Google Alerts did their job, alerting me to a new systematic review published online late last week in the Journal of Human Reproduction Update. Berman is the corresponding author (of course!), and a research associate by the name of Eric Manheimer is the lead author, and together with other colleagues, they have produced yet another fine analysis of tooth fairy medicine entitled, The effects of acupuncture on rates of clinical pregnancy among women undergoing in vitro fertilization: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Of course, as is the case for many acupuncture studies (actually, nearly all acupuncture studies), there is no prior plausibility. Think about it. How on earth would sticking needles into the skin improve the odds of conception? It wouldn’t, and it doesn’t. Through what biological mechanism would sticking little needles into the skin along fantastical “meridians” improve the likelihood of conception when embryos are transferred into the uterus? None that makes any sense, that’s for sure. That doesn’t stop acupuncturists and acupuncture apologists from heavily selling acupuncture as somehow managing to do just that, against all physiology and reality.

So here’s how the systematic review is being sold:

Acupuncture, when used as a complementary or adjuvant therapy for in vitro fertilization (IVF), may be beneficial depending on the baseline pregnancy rates of a fertility clinic, according to research from the University of Maryland School of Medicine. The analysis from the University of Maryland Center for Integrative Medicine is published in the June 27 online edition of the journal Human Reproduction Update.

“Our systematic review of current acupuncture/IVF research found that for IVF clinics with baseline pregnancy rates higher than average (32 percent or greater) adding acupuncture had no benefit,” says Eric Manheimer, lead author and research associate at the University of Maryland Center for Integrative Medicine. “However, at IVF clinics with baseline pregnancy rates lower than average (less than 32 percent) adding acupuncture seemed to increase IVF pregnancy success rates. We saw a direct association between the baseline pregnancy success rate and the effects of adding acupuncture: the lower the baseline pregnancy rate at the clinic, the more adjuvant acupuncture seemed to increase the pregnancy rate.”

It’s hard not to be a bit snarky here and say that if your clinic is doing well with its pregnancy rate, then obviously you don’t need mumbo-jumbo. However, if you’re not doing so well, maybe some bread and circuses will help.

So let’s look at the study itself or, as I like to say, go to the tape (or journal, or whatever). Basically, Berman and company examined sixteen trials with a total of 4,201 participants that compared needle acupuncture administered within one day of embryo transfer to sham acupuncture or no treatment. They left out studies that examined electroacupuncture (a famous bait-and-switch form of acupuncture frequently mixed in with regular acupuncture). Well, actually, not exactly. Their rationale for not using electroacupuncture studies was not what you would think, namely because they didn’t want to mix acupuncture studies with studies involving electricity, which didn’t exist at the time when acupuncture was allegedly invented. Rather, the rationale was that these studies involved studying electroacupuncture as an alternative to conventional anesthesia during oocyte retrieval and the points are therefore not chosen to improve fertility bur rather to reduce pain. Electroacupuncture was okay, as long as its intent was pregnancy. I kid you not. In other words, the authors excluded electroacupuncture, except when they didn’t.

In any case, the methods used were fairly standard systematic review/meta-analysis methodology, and when they were through they had 16 randomized trials. Now here’s the annoying thing. This is a negative study. Oh, the authors, as you can see from the press release, jump, jive, and wail to try to extract something out of it that can fool the rubes into seeming positive, but the bottom line is this. When they looked at the pooled studies, there was no statistically significant difference in pregnancy rates between the acupuncture and control groups. None. Nada. Zero. Zip. And any other word you can think of for “no” or “zero.” Or, as the authors put it, there was “no statistically significant difference between acupuncture and controls when combining all trials [risk ratio (RR) 1.12, 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.96–1.31; I2 = 68%; 16 trials; 4021 participants], or when restricting to sham-controlled (RR 1.02, 0.83–1.26; I2 = 66%; 7 trials; 2044 participants) or no adjuvant treatment-controlled trials (RR 1.22, 0.97–1.52; I2 = 67%; 9 trials; 1977 participants).”

That’s a negative trial. Acupuncture does not improve pregnancy rates. Did I say that enough times? Heck, consistent with what one would expect for an intervention that doesn’t have an effect, the asymmetric funnel plot showed a tendency for the intervention effects to be more beneficial in smaller trials. We see the same thing in virtually all clinical trials, but especially in clinical trials of CAM modalities. Homeopathy, in particular, is notorious for demonstrating this effect. So is acupuncture.

Of course, in so-called “complementary and alternative medicine” (CAM) or “integrative medicine” trials, there’s never such a thing as a negative study. So we have subgroup analysis, the better to seek statistically significant results in smaller pools of patients, where there might be more variability. All too often it’s not clear whether that subgroup analysis is prespecified or cooked up post hoc. To Berman’s credit, in this case, the subgroups were specified before the meta-analysis:

We conducted subgroup analyses on five clinical characteristics that might influence the effect of adjuvant acupuncture on clinical pregnancy success rates: (i) two acupuncture sessions or more than two; (ii) selection of meridian acupuncture points the same as the points selected in the first published trial (Paulus et al., 2002) that evaluated acupuncture as an adjuvant to embryo transfer, and which showed a large effect, or a modified version of this trial’s acupuncture point selection protocol; (iii) control group clinical pregnancy rate (as an estimate of the baseline clinical pregnancy rate) dichotomized as higher [32% or greater, which is the European average of pregnancy rate per embryo transfer (de Mouzon et al., 2012)] or lower; the control group clinical pregnancy rate was also analysed as a continuous variable to test whether the relation was linear and consistent with the findings of the categorical analysis; (iv) explanatory trials conducted to test the effects of adjuvant acupuncture under controlled conditions in which the acupuncture was administered onsite at the IVF clinic or pragmatic trials conducted to test the effects of adjuvant acupuncture delivered off-site, which might better approximate every day, ‘real life’ conditions since most IVF clinics do not have onsite acupuncturists (Arce et al., 2005); and (v) trials that involved a treating acupuncturist who was judged as adequately experienced or not adequately experienced, with such judgments made by acupuncturist assessors who were blinded to the identities and results of the trials.

One wonders what objective criteria these acupuncturist assessors use to judge other acupuncturists as “adequately experienced.” They also prespecified six “risk of bias” domains to be examined: random allocation sequence generation; concealment of allocation of randomization sequence; blinding of patients (i.e. use of sham control); blinding of embryo transfer physicians; incomplete outcome data; and unequal co-intervention. And guess what? These were nearly all negative, too. There was only one exception, which of course was touted in the press release above. Oh, the authors dance around several variables that they describe as “almost” statistically significant, but “almost” only counts in horseshoes and hand grenades (and nuclear weapons). To be honest, these subgroups weren’t even that close to being statistically significant. If I were reviewing this paper, I would have told the authors to cut out at least a couple paragraphs worth of verbiage dancing around these topics, although it is somewhat interesting to note that one of these “almost significant” subgroups was whether or not the physician doing the IVF embryo transfer was blinded to the acupuncture status of the subject.

In any case, there was an inverse correlation between the baseline pregnancy rate observed in a study and the effect of acupuncture. Studies reporting greater than average pregnancy rates (32% or greater) showed no effect of acupuncture. In fact, the risk ratio for such studies was 0.90 [95% confidence interval 0.80 to 1.01]. That’s almost, but not quite, a statistically significant negative effect on pregnancy rates! In contrast, studies for which the baseline pregnancy rate was less than 32%, produced a risk ratio of 1.53 [95% confidence interval 1.28 to 1.84]. Why is this? Who knows? The authors speculate that additional interventions have little or no value when pregnancy rates are already high, but acupuncture can help when pregnancy rates are low, but there are so many factors that determine pregnancy rates, including embryo selection, prevailing practice, number of embryos transferred, and many others. There could very well be a confounder there that the authors didn’t pick up.

There’s a better explanation, or maybe two explanations. First, there is the Hawthorne effect. Basically, it is quite possible that low-performing clinics, knowing that they were being watched carefully in a clinical trial, stepped up their procedures and did a much more rigorous job. That’s one possibility. Another possibility is even simpler. This could simply be regression to the mean. Think about it. The clinics that were low-performing before being involved in a clinical trial got better, and the clinics that were high performing beforehand got a little bit worse. True, the latter wasn’t quite statistically significant, but the trend is suggestive.

The hilarious thing about this study is that, no matter how much Berman tries to argue otherwise, it confirms what we already know. Acupuncture does not work. It does not improve the pregnancy rate. There is no physiological mechanism to think that it should, and this meta-analysis confirms it. The questions of whether a sham control intervention is needed or not, whether multiple treatments are needed or not, whether sticking to the meridians matters or not are all the equivalent of what Harriet Hall likes to call Tooth Fairy science.

Book III: Keep those acupuncture needles away from my lymphedematous arm!

So we’ve had in essence a case report of a horrible complication after acupuncture for headaches, followed by a systematic review/meta-analysis that tries to convince readers that acupuncture can improve pregnancy rates in IVF, even though the clear conclusion based on the studies analyzed is that it does not. Now let’s look at a study that tries to convince you that it’s OK to stick needles where they shouldn’t be stuck.

Lymphedema is a complication of breast cancer surgery that all surgeons who do breast surgery fear. Patients, of course, fear and detest it even more because, after all, they have to live with it. The limb swelling that is the primary symptom of lymphedema comes about because surgery on the axillary lymph nodes (the lymph nodes under the arm) that is part and parcel of surgery for breast cancer can interrupt lymph vessels and cause backup of lymph fluid in the affected arm. This backup has consequences, including skin changes, a tendency towards infections, and, in extreme cases, elephantiasis (which is, fortunately, rarely seen these days as a result of breast cancer surgery). Unfortunately, lymphedema is incurable, and the risk of developing it never goes away after breast surgery.

Lymphedema used to be much more of a problem back in the old days (say, more than 10-15 years or so ago), when surgery for breast cancer routinely involved an axillary dissection, or removal of most of the lymph nodes under the arm. (For surgery geeks, in breast surgery level 1 and 2 lymph nodes out of three levels, unless, of course, level 3 nodes are grossly involved with tumor, in which case they’re taken out too.) Frequently radiation therapy was needed as well, and the combination of axillary dissection and radiation therapy could produce a risk of lymphedema as high as 50%. Of course, in recent years sentinel lymph node biopsy, which involves removing many fewer nodes (usually 1-3) has supplanted axillary dissection for most cases of breast cancer, and, consistent with fewer nodes being taken, the risk of lymphedema from sentinel lymph node biopsy is much lower. However, none of this means that lymphedema isn’t still a problem after breast surgery; it’s just less of a problem.

There are only a few basic strategies for treating lymphedema. These strategies are sometimes referred to as decongestive lymphatic therapy. For the most part, these treatments involve physical therapy, compression sleeves to “squeeze” the fluid out of the affected limb, and sometimes the use of mechanical compression stockings that “milk” the fluid back. It’s all very inconvenient and unpleasant. There’s no doubt that this particular complication can take a major toll on a patient’s quality of life and sometimes even lead to hospitalizations for infection. It might be less of a problem than it was in years past, thanks to the increased frequency of much less invasive surgery, but it’s still a problem. As long as we need to evaluate the axillary lymph nodes in breast surgery, it will always be a problem. That’s why it needs better treatments.

Acupuncture is not one of those better treatments

Not that proponents of acupuncture don’t try to convince people that acupuncture is a treatment for lymphedema. To be honest, knowing the mechanism by which lymphedema develops, I can never quite figure out why anyone would think that acupuncture would do anything for lymphedema. How, pray tell, would sticking needles into the body, often in areas of the body not involved by lymphedema, be expected to cause lymphedema to get better? Yet, acupuncturists keep claiming that acupuncture can be used to effectively treat lymphedema. Indeed, if there’s one image that causes me to cringe when I see it, it’s the image of needles being stuck into a lymphedematous arm, often with the acupuncturist not wearing gloves. That’s why I cringed when I saw a recent study out of Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) examining acupuncture as a treatment for breast cancer surgery-associated lymphedema in the ASCO Post:

Arm lymphedema affects approximately 30% of breast cancer survivors, with rates increasing with longer follow-up and cases presenting well beyond the active treatment period. Lymphedema is observed even with use of less-invasive surgical techniques for staging, and risk is further increased by such factors as radiation therapy, positive lymph node status, increased tumor burden, postoperative seroma or infection, obesity, and increased age. Current treatments for lymphedema after breast cancer treatment are expensive and require ongoing intervention. As reported by Barrie R. Cassileth, MS, PhD, of the Integrative Medicine Service at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center and colleagues in Cancer, acupuncture may be an effective treatment.

The study appeared in the journal Cancer and was entitled “Acupuncture in the treatment of upper-limb lymphedema: Results of a pilot study“. It’s as fine an example of quackademia as I’ve ever seen, its lead investigator being our old friend Barrie Cassileth, the director of the integrative medicine department at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. This time around, it’s acupuncture for lymphedema. Truly, acupuncture is the therapy that can do anything, which is consistent with it being quackery. Certainly, no one has ever postulated a mechanism by which acupuncture can do all the things claimed for it, including (but not limited to) relieving pain, relieving hot flashes, treating infertility, improving asthma symptoms, and, of course, treating lymphedema. What’s the common unifying biological mechanism that could explain therapeutic effects in all these diseases and conditions? There is none, at least none that any acupuncturist has ever been able to explain convincingly to me, nor was any claimed in the ClinicalTrials.gov entry for this.

So what does this study purport to show? It’s a pilot study involving 33 patients with breast cancer-related lymphedema for at least six months but not longer than five years. This time period was chosen to make sure that the subjects were all out of the immediate postoperative period but not so many years out that they started to develop skin complications from chronic lymphedema. These patients all underwent twice weekly 30-minute acupuncture sessions for four weeks as follows:

Alcohol swabs were applied prior to insertion of sterile single-use filiform needles (32-36 gauge; 30-40 mm in length, Tai Chi brand, made in China and distributed by Lhasa OMS, Weymouth, MA) that penetrate 5-10 mm into the skin. A total of 14 needles were inserted: 4 in both affected and unaffected limbs, 2 in acupuncture points on both legs, and 2 in unilateral points on the torso. Selected acupuncture points (Fig. 1) were stimulated manually by gentle rotation of the needles with lift and thrust. The acupuncturists did not intentionally seek to achieve a de qi sensation.

Specific acupuncture points used in this study were determined on the basis of historical context, the published literature, and the consensus of our experienced group of MSKCC staff acupuncturists.[18-20, 34, 37] Many of these acupoints are used to treat pain, weakness, and motor impairment; others are traditionally used to drain “dampness,” a TCM concept similar to edema.

Did I just read what I thought I read? Seriously? The rationale for choosing these points was based on their being related to traditional Chinese medicine concepts to drain “dampness”? This is utter nonsense, the sort of silliness in which quackademic medicine corrupts academic medicine with concepts that have nothing to do with science. Just read about “dampness” in TCM:

In nature, dampness soaks the ground and everything that comes in contact with it, and stagnation results. Once something becomes damp, it can take a long time for it to dry out again, especially in wet weather. The yin pathogenic influence of dampness has similar qualities: It is persistent and heavy, and it can be difficult to resolve. A person who spends a lot of time in the rain, lives in a damp environment, or sleeps on the ground may be susceptible to external dampness.

Similarly, a person who eats large amounts of ice cream, cold foods and drinks, greasy foods, and sweets is prone to imbalances of internal dampness. Dampness has both tangible and intangible aspects. Tangible dampness includes phlegm, edema (fluid retention), and discharges. Intangible dampness includes a person’s subjective feelings of heaviness and dizziness. A “slippery” pulse and a greasy tongue coating usually accompany both types of dampness. In general, symptoms of dampness in the body include water retention, swelling, feelings of heaviness, coughing or vomiting phlegm, and skin rashes that ooze or are crusty (as in eczema).

As I said, none of this has anything to do with science.

So, based on a TCM concept of “dampness” being tortuously related to lymphedema, quackademics at MSKCC subjected patients to acupuncture and measured their limb circumferences. There are a few ways to measure lymphedema. One is water displacement, in which the subject puts her arm into a cylinder of water, and the volume displaced is measured. This method isn’t used much anymore because it’s messy and inconvenient to do, although it is arguably the most accurate. In most cases, lymphedema is measured by comparing the circumference of each arm at different locations defined by anatomy. Generally, this is done in four locations, the metacarpal-phalangeal joints, the wrist, 10 cm distal to the lateral epicondyles, and 15 cm proximal to the lateral epicondyles. Differences of 2 cm or more at any point compared with the contralateral arm are considered by some experts to be clinically significant. The authors used a two-point technique performed by trained research assistants 10 cm above (upper arm) and 5 cm below (lower arm) the olecranon process using nonstretch tape measures, which is said to be as sensitive and specific as any other methods. The median age of subjects was 55, and they were a mean of 3.9 years out from surgery. They were on the obese side, with a mean BMI of 30.4, which is above 30 and thus in the obese range.

The results were as follows. A 30% or greater decrease in arm circumference was observed in 11 patients (33%) and 18 had a reduction of at least 20%, a reduction reported to be across the whole range of severity of lymphedema. One notes that 31 subjects (94%) used other standard therapies during the study, although 30 reported no change in their standard regimen. Now here’s where how you present the data makes all the difference in the world. These percentages seem huge, but you have to remember that the way they were calculated was in terms of the difference between the two arms in circumference, normalized to the pre-treatment difference. If the pre-treatment difference is small, then it doesn’t take much of a decrease in lymphedema to produce a large percentage. That’s why the really telling figure comes from Table 3, which shows that the mean difference between pre-treatment and post-treatment arm circumference was 0.9 cm (95% confidence interval 0.72 to 1.07 cm). That is spectacularly unimpressive, particularly in a population that skews obese. It sure sounds a hell of a lot more impressive when expressed as a percentage.

Of course, the biggest problem with this pilot study is that it was uncontrolled. There is no control group. So we have no idea whether acupuncture had anything to do with the modest decrease in lymphedema reported. I will give Dr. Cassileth credit in that she does acknowledge this in the paper:

Whether acupuncture alone was responsible for this reduction was not evaluable in this pilot study. Our focus was on safety and potential efficacy, as current clinical practice to protect the lymphedematous arm prohibits needling.

Yet she also concludes, unfortunately:

The therapeutic and cost-reduction potential of acupuncture for lymphedema may yield an important tool in the arsenal of lymphedema management. Although randomized clinical trial results await, including our ongoing study, acupuncture can be considered to treat this distressing problem confronted by many women with no other options for sustained reduction in arm circumference.

This study is not good evidence that acupuncture works for lymphedema. There is no reason from a standpoint of prior plausibility informed by biology to think that acupuncture would do anything for lymphedema. On a Bayesian basis, exceedingly low prior probability plus an equivocal result (and, yes, this result is equivocal) equals a very high likelihood that the effect observed is a false positive. Even worse, the randomized clinical trial being carried out isn’t one that is likely to provide much of an answer. It’s a phase 2 clinical trial comparing immediate acupuncture to wait list for six weeks, after which wait listed subjects will cross over and receive acupuncture for six weeks. In other words, everyone in the study will receive acupuncture. I mean, really. Why are they even bothering? This study is unlikely to provide strong evidence that acupuncture works. Most likely, it will be another equivocal acupuncture trial. Of course, the ironic thing is that the crossover design was probably necessitated by the seemingly “positive” result of Cassileth’s currently reported trial. The IRB probably wouldn’t approve a no acupuncture arm in light of that, because then there wouldn’t be clinical equipoise.

Oh, the ironies of quackademic medicine, when the inevitable false positives that occur when treatments of low prior probability are tested in clinical trials complicate the next steps! It’s just infuriating how much time and resources are being wasted on studies that are so highly unlikely ever to produce useful results.

The Trilogy is complete

So what have we learned today? First of all, we’ve learned that, contrary to the claims of its practitioners and apologists, acupuncture is not perfectly safe. No one’s claiming that it’s particularly dangerous, but it’s definitely not perfectly safe. On rare occasions, it can even cause serious complications. Next, consistent with the overwhelming clinical evidence that acupuncture does not work, we’ve see two studies that desperately try to convince you that acupuncture helps infertile couples undergoing IVF to conceive and that it can be used for lymphedema. In the case of IVF, the study showed exactly the opposite of what the authors claim it shows. It shows that acupuncture doesn’t work for IVF. Finally, we learned that, despite what Barrie Cassileth says, there is no good evidence that acupuncture works for lymphedema, just as there is no good evidence that acupuncture works for anything. Even if its risk is very small, it is all risk and no benefit, and there is no science-based reason to ever use it.